por Rob Painting

By and large, the mainstream media has a pretty dismal record in reporting about climate change, and a recent op-ed in the National Post, written by Lawrence Solomon, continues in this vein. In the piece, Solomon makes light of the dire threat global warming poses to the continued existence of the Amazon rainforest. After the IPCC Amazon non-controversy, it's probably time to look at the issue in a bit more depth, and debunk Solomon at the same time.

In his article, Solomon highlights a sober assessment of the implications of the extreme 2005 and 2010 Amazonian droughts, from Simon Lewis, a leading Amazon researcher, based at the University of Leeds. To which Solomon writes:

"Today, just three months after that dire outlook, the doom and gloom is lifting. The Amazon and its species have made a dramatic comeback, so much so that the river populations of dolphins now exceed pre-drought levels, even in one of the hardest hit drought areas"

Is it really that simple?. Have scientists overstated the case? Can dead trees really spring back to life? And can river dolphins really breed so astonishingly quickly?. Well, leaving aside the dolphin issue, the answer is a resounding 'no'. Here's where a bit of background information is useful:

Seasons in the Amazon

Like many tropical regions, a wet & dry season occurs in the Amazon, this seasonal variation is a consequence of the Earth's tilt, relative to its plane of orbit around the sun, and intense heating of the sea surface in the regions at the equator. See illustration below:

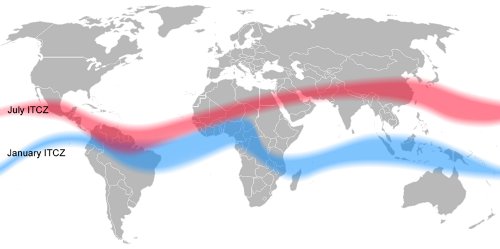

The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), is a band of low pressure circling the equator, which is associated with strong rainfall. In the case of the Amazon, it brings moisture into the basin from the Atlantic sea surface. In the northern hemisphere (boreal) summer (June/July/Aug), the ITCZ travels north to the area of most intense heating, this deprives the Amazon of rainfall. In the southern hemisphere (austral) summer (Dec/Jan/Feb) the ITCZ is pulled south again, bringing the rains with it.

Figure 2 - relative position of the ITCZ for the northern (July) and southern (Jan) hemisphere summers. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

This annual migration of the ITCZ, as it follows the sun, leads to the typical Amazon seasonal rainfall pattern we see below:

Figure 3 - Long-term mean (1979–2000) Climate Prediction Center Merged Analysis of Precipitation (CMAP, Xie and Arkin, 1997) seasonal precipitation totals (in mm) for December–February (left) and June–August (right). From Cruz Jr 2007.

The Amazon & ENSO

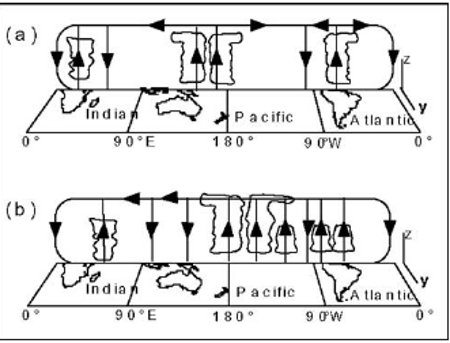

On top of the seasonal cycle is the ENSO cycle, La Nina and El Nino. El Nino often brings drought because the warming sea surface in the eastern tropical Pacific pulls the Walker Circulation induced rain toward the Pacific Ocean, and the Amazon therefore dries out. The lack of moisture and evaporative cooling at the surface causes the land to heat up more than normal, amplifying the drought. During La Nina, the Amazon typically sees higher-than-average rainfall and cooler-than-average surface temperatures (Foley 2002).

Figure 4 - Changes in the Walker Circulation during (a) La Nina and (b) El Nino periods. During La Nina, the Amazon region experiences higher-than-average precipitation. During El Nino, the main convection center shifts to the central Pacific, convection over Amazonia weakens, and the precipitation totals drop below average. From Foley 2002

This is a somewhat simplified version of the situation, for instance parts of the southern Amazon are drier than normal in both La Nina and El Nino phases (implications of which we'll discuss later), but it describes the general rainfall pattern for the majority of the Amazon.

Context makes all the difference

With the benefit of background knowledge, we can see that Solomon's suggestion, that high CO2 levels ended the drought, is ridiculous. It's unsurprising, given we are still in a La Nina phase, and the Dec-Feb period is the Amazonian wet season, that the 2010 drought in the Amazon ended some months ago. Scientific concerns are not that drought would last forever, but that global warming might induce recurring and intensifying episodes of Amazonian drought, eventually resulting in die-back of the forest.

The recent Amazonian drought, was not terminated by high levels of CO2 in the atmosphere, but by the onset of the wet season, amplified by La Nina. Increasing levels of CO2 present a danger to the future viability of the Amazon, but to understand why, we need to look at the mechanisms thought to be driving the changes.

Nota: O Conexão publicará em breve um novo capítulo deste trabalho: "Climate model simulations of Amazonian 'die-back'". Mantenha-se atento.

0 comentários:

Postar um comentário